/assets/images/provider/photos/2406471.jpeg)

A woman in a private online group of middle aged women recently asked the rest of us how to manage her chronic urinary tract infections. The advice she received, from dozens of menopausal and perimenopausal women dealing with similar and seemingly intractable tracts, ranged from PH balanced vagina wash to prophylactic antibiotics after sex, orange juice, cinnamon capsules, vitamin C/ascorbic acid, water based CBD lube, cranberry pills, Angocin, D mannose, cotton undies, and to more misinformation and snake oil than I had the time or patience to scroll all the way through because my head was exploding.

Normally I’m more of a lurker in this group, not a participant, but I felt compelled to type a comment this time, urging the poster to contact Dr. Rachel Rubin, an activist urologist who reached out to me over Twitter DM after I published this story in The Atlantic on estrogen and the female brain, which led to a discussion about chronic UTIs––mine––which ended my decade of unnecessary suffering.

Suffice it to say, we, the menopausal, should not have to resort to asking strangers on Facebook how to treat our chronic UTIs. Nor should it have taken a female urologist reaching out over Twitter to tell me that vaginal estrogen could cure my chronic urinary tract infections. But that’s what happened, and it changed my life. Not only did my UTIs disappear, my brain fog lifted, I slept through the night, my hot flashes vanished, my mood improved, and I felt, for lack of a better simile, like myself.

“We have beyond failed women…and all vulva owners,” said Dr. Rachel Rubin, the assistant clinical professor of Urology at Georgetown University who DM’d me. Her goal? To educate the public and right the wrongs––doctor by doctor, vulva by vulva––foisted upon middle-aged women as a result of the media hype surrounding the Women’s Health Initiative: a task, she said, that can often feel like screaming into the void. “It was so powerful, that messaging that came out––saying hormones, particularly estrogens, are dangerous––that even the researchers performing the study have been trying to scream that it's actually much more nuanced. But nobody is listening.”

In fact, participants in the billion dollar, NIH-funded WHI study who’d had their uteri removed, like me, had a decreased risk of getting and dying from breast cancer when on systemic estrogen therapy. And when the data is separated out by age, those women who’d started taking hormones during that key but small menopausal window between the ages of 50-60 had a 30% reduction in all cause mortality. Furthermore, women who were given only local vaginal estrogen, which never enters the bloodstream, had no increased risk of any cancer or cardiovascular disease whatsoever.

“We are not taking away women's gummy bears or cigarettes,” said Dr. Rubin, explaining that a diet high in sugar, smoking, consuming two alcoholic beverages a night, and even being a flight attendant all pose a far greater statistical risks of breast cancer and heart disease than that found in women who started taking the oral estrogen pill after the age of sixty.

So why do so many of us with uteri––even those of us who consider ourselves to be relatively well informed––not know any of this? Simple. Our doctors, untrained in menopausal medicine and swayed by the media hype surrounding the WHI, don’t know it either. And until the publication of recent books such as Jen Gunter’s Menopause Manifesto and the Twitter activism of doctors such as Dr. Rubin and Dr. Jocelyn J. Fitzgerald, the very real and debilitating symptoms of menopause were treated––if at all––as either minor annoyances to be endured or the butt of comics’ jokes.

Meanwhile, as we sit here in the dark––sweating, sleepless, scattered, saturnine, and swamped by too many UTIs to count––science has been marching on. Today’s recommended MHT (menopausal hormone therapy, the preferred terminology replacing HRT) have expanded beyond the oral Premarin pills given to the women in the WHI study to include systemic transdermal treatments––gels, patches, creams, and rings––that can more safely alleviate most or all of the symptoms of menopause. Local/non-systemic treatments can also be delivered directly into the vagina to prevent recurrent UTIs and vaginal dryness. “A birth control-style synthetic estrogen pill taken by mouth which goes through your whole body is totally different than a local vaginal estrogen that doesn't increase your blood levels,” said Rubin. “They are totally different and should have different warning labels, but the FDA won't allow for the nuance. Hormones for menopause are not all the same.”

She likened this apples-to-oranges absurdity to comparing birth control pills to condoms: “Though it’s rare, we know birth control pills can cause blood clots. So condoms should have a warning label that says they also cause blood clots, because condoms and birth control are both contraception.”

According to the National Women’s Health Network, nearly half of all women will experience at least one UTI in their lifetime; nearly half of those infections will recur; and all of these UTIs will result in 8-10 million office visits, 1-3 million emergency department visits, and 100,000 hospitalizations each year. In January, 65-year-old former Bond girl Tanya Roberts died from a UTI, along with an estimated 13,000 women per year.

My recurring UTIs began soon after I had a hysterectomy in 2012, to treat a case of adenomyosis that had been going on for sixteen years because like most women suffering from adenomyosis, I had no idea I had it. Nearly every time I had sex after that hysterectomy, I’d feel burning pain and a constant urge to pee afterward. My primary care physician put me on a prophylactic dose of Nitrofurantoin, an antibiotic, which is the accepted course of care recommended by even Planned Parenthood.

Sometimes this prophylactic approach worked. Mostly it didn’t, and I’d have to start taking another course of antibiotic. Soon, those antibiotics grew as ineffective in my body as they are quickly and alarmingly becoming worldwide. Cipro and/or abstinence became the only surefire ways to combat my nonstop infections. When I told Dr. Rubin about all of this over Zoom, I could see her shaking with anger. “Recurrent antibiotic use is associated with a much higher breast cancer risk than vaginal estrogen!” she said.

I did not know this. But I did, in 2013––a year and a half after my hysterectomy––get diagnosed with stage 0 breast cancer. Or, rather, one doctor diagnosed my lump with stage 0 breast cancer, another called it atypia. I still don’t know what to call it other than possibly avoidable.

After Dr. Rubin found me on Twitter, she urged me to either drive down to DC to meet with her or to find a doctor near me who specializes in menopausal medicine.

This, it turns out, is not such an easy task. Even in doctor-dense New York City. According to a 2018 Mayo Clinic study, which looked for menopause knowledge gaps in the training of U.S. residents in family medicine, internal medicine, and OB/Gyn––those doctors, in other words, who should be on the front lines of menopausal medicine––only 6.8% of respondents reported feeling adequately prepared to manage patients in menopause. And a full 20.3% reported having never attended a single lecture on menopausal medicine whatsoever.

I poked around online and made a bunch of fruitless calls for a couple of hours––“Does Dr. So-and-So advise hormone therapy to his middle-aged female patients? No? Okay, thanks, bye…”––until I found my needle in a haystack: Dr. Molly McBride, a gynecologist in my insurance plan who specifically listed menopausal medicine as one of her specialties.

Dr. Molly McBride

“I am self-taught,” said Dr. McBride, when I asked about her expertise in menopause. “By studying. And reading research. And figuring out what was safe, what to give. By reading articles, going to conferences.” Dr. McBride, who holds the tenets of narrative medicine sacrosanct, spent nearly a half hour listening to the long story of my ladyparts: not only the adenomyosis and hysterectomy but a trachelectomy followed by near death from vaginal cuff dehiscence, the latter two a result of the data gaps and medical gaslighting, respectively, that plague women’s health. Aside from my chronic UTIs, I told her, I was also suffering from other debilitating menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, difficulty sleeping, and word recall issues.

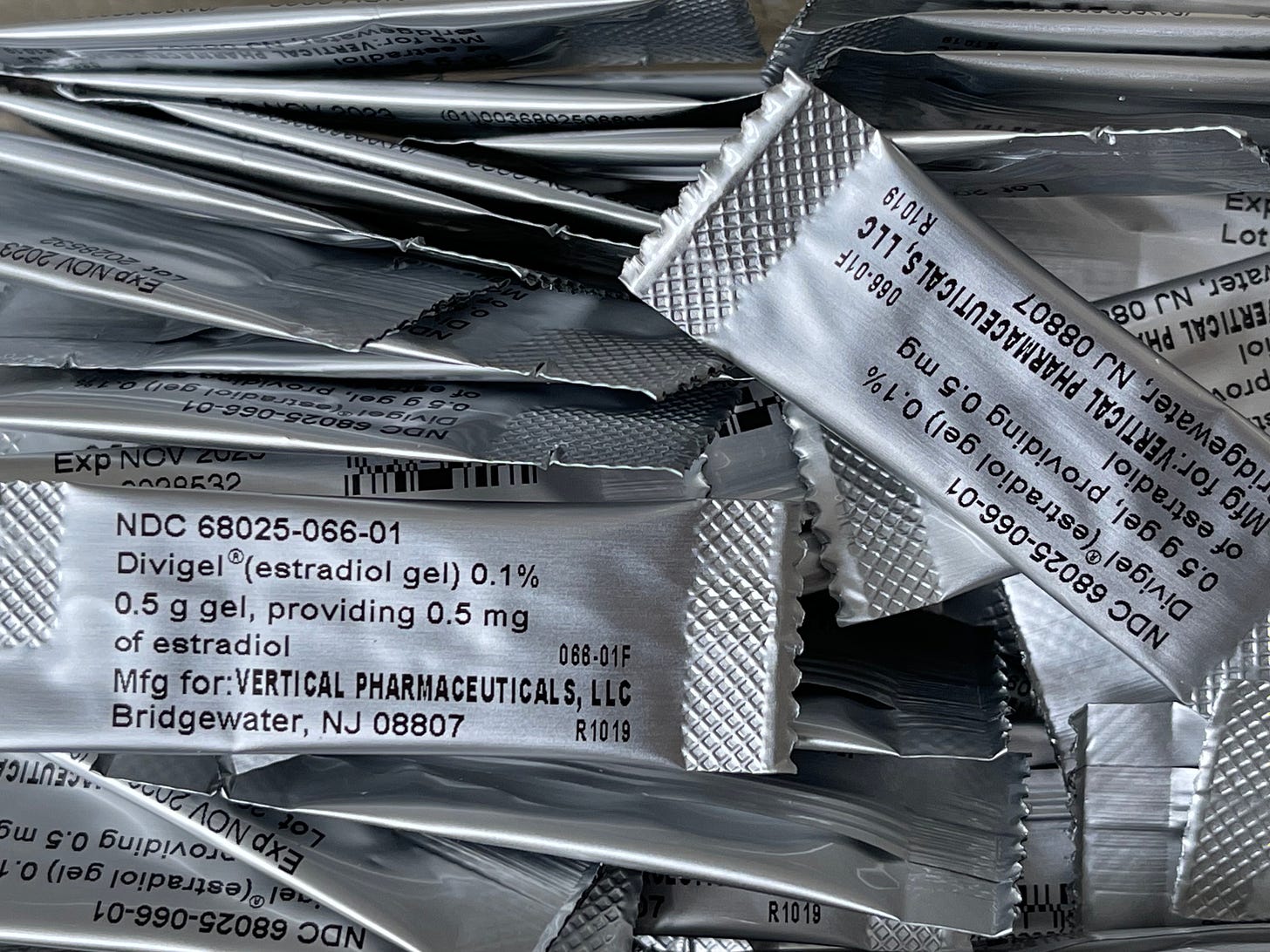

She prescribed a low does (0.5 Mg) of Divigel, a topical systemic estradiol that is rubbed into the thigh every morning. But first I had to fight my insurance company to cover it. Why? Because if our doctors are ill-informed about the realities of and treatments for menopause, our insurance companies are even moreso, plus, needless to say, they are driven by saving dimes, not dames. They suggested I take a less expensive estradiol pill instead of the gel. “No!” said Dr. McBride. “Absolutely not. It’s a completely different medicine!” Transdermal estradiol improves sexual function when compared to oral estrogen, she explained, and it does so with less risk.

After months of arguing with my insurance company, I finally started on Divigel at the end of March, 2020, after another UTI placed me, twice, in a maskless, Covid-infected urgent care, with obvious and frightening repercussions. I’ve been asymptomatic of the multiple scourges of menopause ever since, including not having had a single UTI since April of 2020.

Yes, said both Drs. Rubin and McBride, that’s great, but it’s one thing for one woman––and a science writer at that, who’s trained to question and dig––to find relief with caring physicians trained in menopausal medicine. It’s quite another to convince all middle-aged women, their insurance companies, and the entire medical community to completely change the way they treat chronic UTIs and other symptoms of menopause. “Physicians are very fearful of any possibility of any risk of a negative outcome,” said McBride. “It’s easier for them to just say ‘No, I don't prescribe MHT’ instead of truly evaluating each patient and creating a personalized approach and taking a chance to help women.”

An estimated 1.3 million American women enter menopause every year. That we must resort to asking Facebook friends how to manage its symptoms is as sure a sign as any that medicine continues to fail us. Money and organizational muscle to get the word out about proper hormone treatments could help (I’m looking at you, Planned Parenthood and ACOG). As would better training in our medical schools. My daughter, who is considering becoming an OB/Gyn after rushing her hemorrhaging mother to the hospital for emergency surgery to repair the ruptured vaginal cuff, just entered her first year of medical school. I implored her, as I was dropping her off at orientation, to make sure she either learns about menopause or insists that her professors teach it (I’m looking at you, University at Buffalo.) We also need further studies proving the benefits of menopausal hormone therapy, so that women and doctors alike see estrogen as the first line of defense in their arsenal.

If Dr. Rubin has her way––and now that I know her better, I believe she will––every woman, on the day she turns 45, will get a colonoscopy, a mammogram slip, and a prescription for vaginal estrogen. Until then, Dr. Rubin will keep posting the latest research on Twitter and reaching out to strangers over DM, while the stigma and fears caused by the media hype around the WHI continue to cast their long, paternalistic shadow.

“In trying to protect women,” said Rubin, “we are killing them.”